AI-Generated Creatives: How to Use Them Wisely to Avoid a Legal Action?

The creative industry faces a radical new challenge: the rise of machine-created artwork. All of a sudden, technology has advanced to the point that bespoke “art” of genuine aesthetic interest (or at least commercial utility) can be conjured up by a computer – on demand, instantly, and for free.

Artificial Intelligence text-to-image generators create digital images based on natural language text or original image inputs. DALL-E 2 is a leading image generation engine. Other text-to-image AI platforms include Midjourney, Google’s Imagen and Parti, and Microsoft’s NUWA-Infinity.

These products rose to prominence in 2022, largely due to the influence of Stable Diffusion created by StabilityAI. Images generated by AIs have already started to be used commercially, including on the covers of The Economist and Cosmopolitan magazines — and, of course, quick and money-saving advertising creatives.

However, AI-generated images present novel legal challenges and uncertainties related to copyright. Here are the four main questions that arise:

- Who is the author of an AI-generated image, and who can hold the copyright on such a creative?

- Can an AI image infringe on the rights of artists?

- Do AI generators owners have any legal rights to the images they produce?

- How can you legally use AI-generated images for commercial purposes?

Although the subject remains very vague, we tried to shed some light on the current legislation and make it a bit clearer.

With the help of Nikolaos Ioannidis, AdTech Holding’s lawyer, we prepared research that will help to sum up the general approaches to this matter — and answer the questions above.

Table of contents:

Who is the author and copyright holder of AI-Generated Works?

–United Kingdom

–United States of America

****Legal case: “Zarya of the Dawn” by Kristina Kashtanova

****Legal case: Naruto vs. Slater

–The European Union

Can an AI creative infringe on the rights of artists?

–AI vs. image license companies

–AI vs. artists

****Legal Case: Graham vs. Prince

AI Generators stance on licensing works

Using AI images: best practices

Conclusion

Who is the Author and Copyright Holder of AI-Generated Works?

Basically, a work must be ‘original’ to attract copyright protection. ‘Original’ means that it must ‘reflect the author’s personality as an expression of his free and creative choices.’

The stumbling block here is the definition of these ‘choices’ degree in the legislation of the particular country. In other words, while some copyright laws acknowledge humans as co-creators of AI images, others have a different stance.

Here is a brief table that quickly describes the situation:

| Jurisdiction | A work created by AI or by a human with AI assistance… |

| UK, Ireland, New Zealand, India | is protected by copyright if it is an original literary, dramatic, artistic, or musical work. |

| USA | is not protected by copyright. Only human-created elements of the work can be protected. |

| EU | can be protected if made by humans with the help of AI but will unlikely have a copyright if produced entirely by AI. |

And let’s now overview how it happens in various jurisdictions in more detail.

United Kingdom

In the UK, copyright law protects original literary, dramatic, artistic, and musical works, as well as films, sound recordings, broadcasts, and published editions. For a work to be original, it must be the author’s own intellectual creation. This means the author has made free and creative choices, and the work has a ‘personal touch.’

So, the main condition for the work to have a copyright is the original human creativity. With AI, we have two possible options to consider:

1. When work was done by a human but with some sort of AI assistance

According to UK law, creativity, as mentioned earlier, remains even with AI assistance. For example, your camera has embedded AI tools that enhance the photo. However, the picture you take still expresses your idea and is considered an artistic work — that has all the rights to be protected.

2. When work was done entirely by AI

The rules don’t dramatically change in this case, too. Currently, the United Kingdom is one of a few jurisdictions providing for copyright protection of “computer-generated” artworks. In this regard, that means that the if the artwork is generated entirely by computer in circumstances such that there is no human author of the work, it still may be subject to copyright under UK law.

The UK Copyright, Designs, and Patent Act of 1988 has a definition that sounds like that:

“In the case of a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work which is computer-generated, the author shall be taken to be the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken.”

So, according to UK law, a human involved in the creation remains the copyright owner — and AI generators are considered just like any other tools an artist can use in his work.

Also, mind some details that depend on the type of work:

- Copyright protects original AI-created original literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works.

- It also protects so-called “entrepreneurial works” that don’t need to be original: broadcasts, films, sound recordings, and published editions. For example, if AI generates a song, the producer of the song recording can obtain a sound recording right.

United States of America

The USA has an opposite approach towards AI-generated works. The official letter of The United States Copyright Office dated February 21st, 2023, states that “an image generated through artificial intelligence lacks the ‘human authorship necessary for protection.’

Thus, artworks created entirely by the software can’t hold any copyright protection. This law is also supported by another guidance from the Office, dated March 16, 2023. It states that the term ‘author,’ used in the Intellectual Property Clause of the U.S. Constitution and the Copyright Act, ‘excludes non-humans.’

The conclusion is the following: in the USA, an author must exclude AI-generated content from their work and can obtain copyright exclusively for its parts created by humans. If the author fails to disclose the AI-created portions of the work, the copyright registration might be canceled.

Legal Case: “Zarya of the Dawn” by Kristina Kashtanova

In September 2022, the US Copyright Office (the “USCO”) granted a first-of-its-kind registration for a comic book generated with AI assistance, which was rather surprising and revolutionary. Kristina Kashtanova, the artist of Zarya of the Dawn, claimed to be the first person to have been granted copyright for an AI-created work.

However, after a couple of months, USCO discovered that AI did the visual part of the comic book. In the end, they reviewed their decision and canceled the certification — but issued a new one, which protected the text part of the work and other original elements.

As Kris explained, the USCO had asked her to provide the details of the process, showing that there was substantial human involvement in the process of creation of this graphic novel. Once she failed to do it, the copyright decision was changed — which makes us suppose the main point that matters is the level of human engagement in the creative process.

Thus, entering the text prompt into an image generator won’t qualify as an act of authorship. However, a serious modification of AI work might reach a degree that meets the copyright protection standard.

The Zarya of the Dawn case is still active — Kashtanova has been granted 30 days to appeal USCO’s decision, and her current copyright is still active. Her lawyer has already submitted a letter to testify regarding the human involvement in the creation of AI art.

One of the arguments for this is that the process was ‘essentially similar to the artistic process of photographer’s selection of a subject, a time of day, and the angle and framing of an image.’

We will keep an eye on the case as its final outcome will definitely bring more clarity to the current AI copyright questions.

Legal Case: Naruto vs. Slater

As we already mentioned, only natural or legal persons can be authors of copyrighted works. This was demonstrated in another intriguing US case of Naruto vs. Slater (aka the ‘monkey selfie copyright dispute’).

The photographer David Slater set up his camera in the habitat of Celebes crested macaques. One of the monkeys, Naruto, was fascinated with the camera and took several selfies while playing with the gear. These selfies were published in newspapers.

Later on, PETA (acting on behalf of one of the macaques in the selfies) sued Slater for using the images. According to them, the copyright belonged to the monkeys that took the selfies. Finding in Slater’s favor, the Appeals Court affirmed that animals do not have legal standing to own copyright or sue for infringement under US law.

Thus, an AI ‘author’ may similarly face issues of legal standing in relation to copyright works.

The European Union

Generally, the EU copyright law requires one to fulfill two conditions to protect a work:

- The creation must be a “work.” In short, it means this creation is ‘original in a sense,’ expresses the author’s intellectual effort, and has their personal touch.

- A copyright holder must be the original author of the mentioned work or have obtained the rights by transfer. The author means human — so if the work was done with the help of any other tool, like, say, a photo camera, it still expresses a human’s idea and ‘creative choice.’

So can AI be considered as ‘any other tool’? In 2020, the European Commission proposed a “four-step test” to help find out if a creation made with the help of AI can be treated as ‘work’:

- Step 1 – Production in the literary, scientific, or artistic domain;

- Step 2 – Human intellectual effort;

- Step 3 – Originality/creativity (creative choice);

- Step 4 – Expression.

Thus, the situation in the EU is the following: AI creations made by humans with some degree of AI’s help can be classified as ‘work’ and so can be protected by copyright. However, creations done entirely by art generators are unlikely to qualify as ‘work’ that can hold copyright.

Note: this four-step test doesn’t bind to the Court of Justice of the European Union — so there might be further changes and developments regarding the AI question.

Can an AI Creative Infringe on the Rights of Artists?

Depending on the legislation and a particular case, the author and the first copyright owner can even be a person who just sets the parameters for image generation. However, the next question is how this image was created — and who else could possibly be involved.

To generate a “new” image, an AI must first be trained to understand text inputs and know what an image matching that text looks like. In basic terms, AI models are “trained” to do this by processing existing images to identify particular patterns.

This ‘training’ requires huge amounts of high-quality data — for example, images, if we speak about visual art. Many of these images are protected by copyright — even if they are generally available to view online. If you want to use these images commercially, you must obtain a license first.

So is using these images for training AI without the owner’s consent considered infringement?

There is no certain reply yet — however, several legal complaints have already been raised.

AI vs. Image License Companies

On 17 January 2023, Getty Images (an image licensing company) announced it was commencing UK legal action for copyright infringement against Stability AI. The reason for the lawsuit was the following: Getty claimed that Stability AI scraped images from its stock without consent to train AI models.

It turned out that the AI generator copied more than 12 million photos to train its Stable Diffusion AI image-generation system — without purchasing any licenses. The outcome of this action is still pending — so the final Court’s decision is a big intrigue, as it might create a base for new practices and laws.

AI vs. Artists

In the US, several artists launched a similar claim against Stability AI and Midjourney. They alleged the companies of the same abuse: using copyrighted artwork for training AI models without permission.

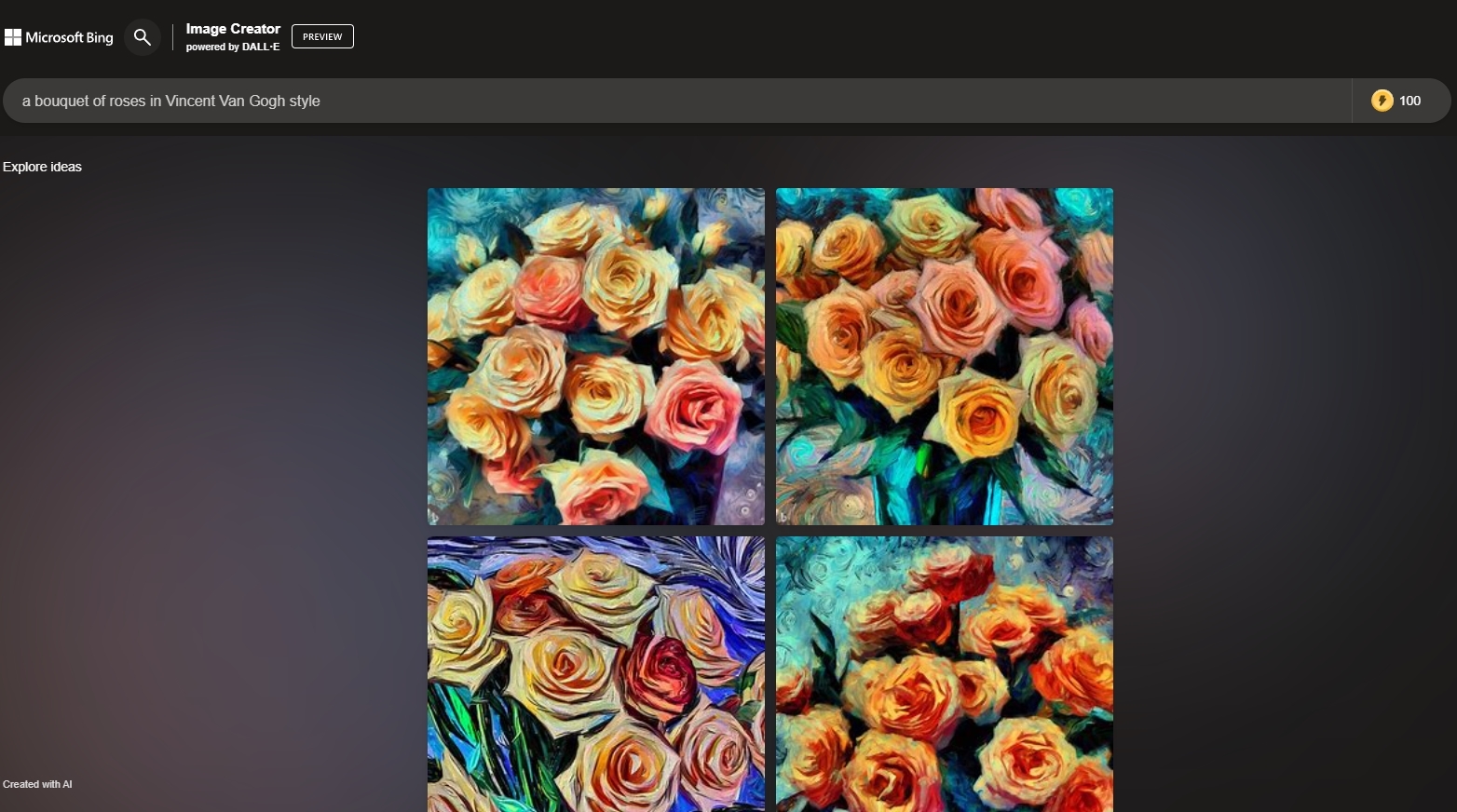

However, this is not the only issue that arises in relation to artists and their rights. A similar concern is that AI-created works can mimic the style and output of particular artists — and many do this on purpose, like here:

Van Gogh’s paintings are in the public domain, so the prompt above does not abuse any of Vincent’s rights. However, artists whose works are copyrighted are concerned. The worst part for them is that their style is unlikely protected by copyright in most jurisdictions.

Overall, the difference between approaches in various countries creates a pretty difficult situation — and there is still no universally accepted practice about sources for AI training.

Another concern is AI-created works that derive from existing art. New artists often build upon existing creations, but the line between inspiration and appropriation is unclear — and becomes almost nonexistent when it comes to AI art.

Let’s look at one of the prior cases — it is not related to AI but can give some hints.

Legal Case: Graham vs. Prince

In 2017, photographers Donald Graham and Eric McNatt sued the well-known appropriation artist Richard Prince for infringement.

Prince took a screenshot of Graham’s photograph published on a third-party Instagram account. The screenshot also contained Prince’s comment — and later, it was represented in an art exhibition.

Prince claimed his work to be ‘transformative,’ which means that he added a novel view and a new message. However, the court disagreed with this argument — and stated that the comment hadn’t significantly altered Graham’s work.

Based on this case, we can conclude that AI artists can unlikely rely on fair use — unless their art sufficiently differs from the original image.

AI Generators Stance on Licensing Works

So you created a work with the help of AI, and you suppose it qualifies for fair use terms. But can you still use it for commercial purposes? This question is mainly about the terms of a particular AI generator — and here is what the top popular ones suggest.

OpenAI (ChatGPT and DALL-E owner):

- allows using your content for any purpose unless it violates or infringes any person’s rights or infringes

- prohibits claiming that a human created an AI’s work

- prohibits using its services for discovering the source code or developing AI models similar to OpenAI

- gives you the right to own the images you create with DALL·E, including the right to reprint, sell, and merchandise

You can read the full T&C here.

Midjourney has a slightly different approach:

- a user owns the content created, provided it was created in accordance with Midjourney’s agreement, excluding upscaling the images of other authors.

- if the user is a company with more than $1,000,000 USD a year in gross revenue, it must purchase a “Pro” membership license to own the content created.

- if a user hasn’t purchased a membership, they don’t own the content created. Instead, Midjourney grants such a user a license to the content under the Creative Commons Noncommercial 4.0 Attribution International License (the “Asset License”).

Thus, copyright ownership in Midjorney neural network is subject to a respective license purchase.

You can read the full T&C here.

Overall, certain AI-based creatives generator services are ready to assign to you all the rights in the output works. However, it all may come with particular limitations so mind the terms and conditions.

Using AI images: best practices

So, how to ensure your ownership of copyright, tackle infringement, and use the images internationally? Here is a brief framework you can use before you utilize any AI creative you produce:

- Ensure that your AI generator license clearly states who owns the creatives and what you can do with them.

- If you use AI images as part of projects involving third parties, the contract with third parties should also consider the legal status of AI images.

- Where AI images are to be used internationally, it would be wise to consider how local laws treat AI images.

Note: The legal status of AI model training is still not so clear in many jurisdictions. Thus, if there’s a new case of unlawful use of the data for training, it may create further uncertainties about the legal status of the generated images.

Conclusion

The boundaries of copyright and particular authorship of AI-generated works are not yet clear. However, the critical question is now apparent. It is

‘What is the level of human involvement in a certain creation?’.

As AI develops, a clearer model of authorship may emerge. There are a number of policy grounds for this, including providing economic incentives to create and maintain AI models/software.

In short, questions of authorship and originality remain the main barrier to copyright subsistence in AI-created output. Overcoming the issue of “whether our creations can create” through legislative or other means will be key to protecting such works.